An intermediate topic, so maybe I’ll start off with some basics, and work my way up:

- The Three Basic Points of View:

The three point of views (POVs) that we were taught in high school were: first person (“I” thought it was a good idea), second person (“you” didn’t stop me), and third person (“he” put us both in detention). These are pretty well understood.

- Limited or Omniscient:

First person is usually limited, in that the narrator can only talk about what the point of view character sees. (“I felt a wet splat against the back of my head and spun around, but Jessie looked coolly innocent”). It would be slightly jarring to go omniscient (“I watched the blackboard intently, determined to limit myself to one detention, while behind me, Jessie smugly wedged a cool saliva-soaked scrap of tissue into a straw”). Maybe you could get away with it, if it was a memoir and separated in time (so the author would know more than they did in the moment), but it’s not commonly done.

The choice is a bit more flexible in third person, though. It used to be quite popular to use omniscient in third person. One of my favorite books, as I understand it, Ender’s Game, was reportedly written with a bit of ‘head-dipping’ originally, switching from one character’s POV to another within a scene. But in recent years, especially in YA, it seems as if third person limited has become much more popular.

It should be noted, though, that switching POVs is not quite the same as omniscient. For example, many epic fantasy novels have different characters as the stars of different chapters, and a point of view character in one chapter may be distant and unknowable in another. (Chapter One: “Reggie stared with stomach-churning hate heart at the root of all his detention misery, the delinquent Jesse Jamone.” Chapter Two: “Jesse smiled smugly, one finger twirling her hair. She knew what it meant when boys stared at her. Her plan was working.”)

So just for the sake of completeness, what would a clear omniscient third person example be? (“The two fidgety lovebirds had no idea that a class A meteor hurtled at the roof of the school at 7,000 miles a minute.”) He he.

PS. Pretty much nobody uses second person, or should, so I’m skipping that.

Okay, enough of the basics. There’s a final dimension, especially relevant for the third person limited point of view choice, and especially in recent writing trends. It’s become quite popular:

- The Electric Fan (Third Person Limited POV).

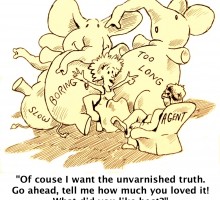

The last dimension to consider in writing third person is how limited or distant your point of view should be. In other words, how firmly embedded inside the character’s head. Are you telling the reader how the character feels, or are you saying their thoughts out loud, as if the reader was sharing the main character’s cranial space? Are you describing the rain, or letting the reader feel it slap their cheeks? This ties into the ideas of “unpackaging your writing”, using all five senses, and “showing not telling”. All of which are post-worthy. But basically, you want the reader to be very close to your character, have them live in their skin, rather than watch from afar.

So let’s assume you think it’s worthwhile to attempt this. Which, by the way, is often easier for people to achieve by writing in first person. For some reason it just comes more naturally. NY best-selling author Jim Butcher says repeatedly that he has more success writing in first person than third, despite valiant efforts otherwise. But third person limited close might still be worth attempting, for example, if you want to write a multiple POV epic fantasy, while still keeping that emotional attachment.

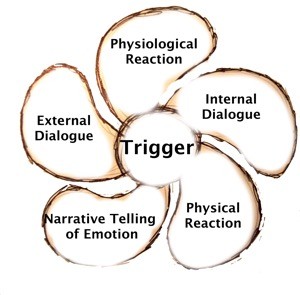

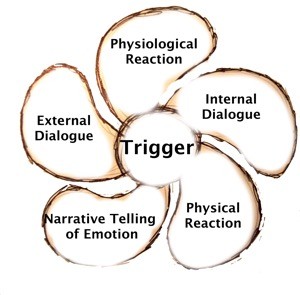

But as I’ve found, in my efforts, easier said than done! And recently, I realized that my electric fan diagram, below, might help my efforts. It is intended to provide a range of ways that a character can react to a triggering event (a line of dialogue, plot setback, or emotional blow), using techniques that keep the scene in close POV. You don’t have to use every one, every time, but it’s helpful to think of what parts of the fan might work at different times.

In a recent short story, when I wrote the character’s reactions, I checked the fan to see what close POV techniques I could use and found it helpful, even though I edited some of the sentences back out later. It gave me a good place to start.

The ‘Parts of the fan’:

- Internal Dialogue

- Narrative telling (emotion, consequences, significance, something that improves the scene through clarifying or amplifying)

- External Dialogue

- Physical Sensations

- Physical Actions (supporting emotional reaction).

Example:

(Continuing with our poor hero, Reggie)

Getting hit by a meteor hurts. A lot. And then it doesn’t. (Narrative Dialogue)

All around Reggie was darkness and stars. A small shimmer of light behind. He got scared. (Narrative Telling)

“Are you there, God?” he whispered. (External Dialogue)

Pain jabbed his back. Hard. Like a rigid finger. (Physical sensations)

His muscles locked. (Physical actions)

“Stop talking to God, jackass, and open your eyes.” (Dialogue)

Jesse. (Internal dialogue)

I hope the electric fan provides you some value. I found it to be a good reminder for me. The pieces of the fan help provide enough emotional insight to make your character feel human, with enough diversity in tools to keep the pace quick and the technique less heavy handed….

And what awaits Reggie and Jesse?

No idea. 🙂 But I feel a second meteor might bring their POV struggles to a worthy end…